FHIR emerged as a solution after years of challenges and limitations with previous healthcare data standards that failed to meet the evolving needs of the industry. FHIR, or Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, was created around 2011. To understand why it came into existence, you have to look at what came before it and why those earlier attempts didn’t work out.

The HL7 standards

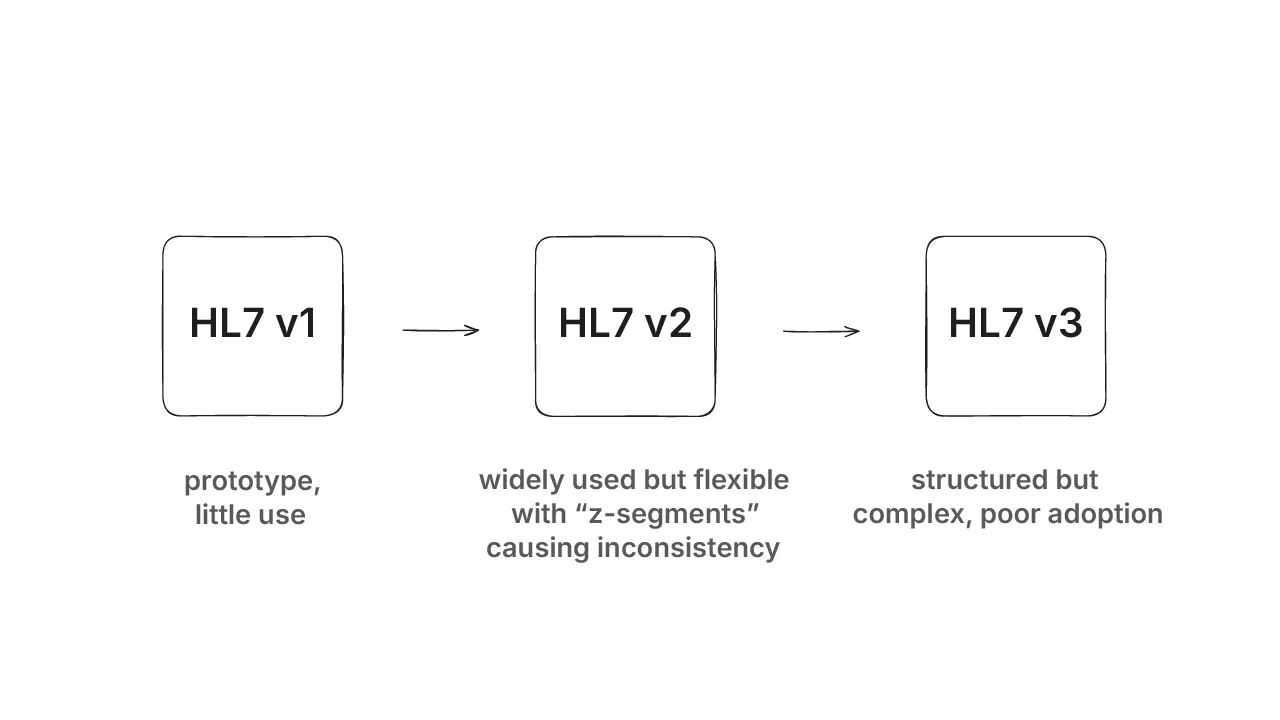

HL7 (Health Level Seven), the organization behind FHIR, has been working on healthcare data standards for decades. It started with what we now call HL7 Version 1 essentially a prototype, and was never widely adopted.

Then came HL7 Version 2 (v2) which actually took off and is still in use today. It offered a lot of flexibility, which was great at first, but that same flexibility eventually became its biggest drawback. Different systems started adding their own custom “z-segments,” which made it hard to achieve true consistency across organizations.

To solve the problems with v2, HL7 introduced Version 3 (v3), this time built on a more formal modeling approach called the Reference Information Model, or RIM. In theory, it was cleaner and more structured.

But in practice, it was just too complex and most developers found it difficult to implement. The few organizations that did adopt it struggled to maintain it.

So now the industry was stuck between two options:

- v2, which was being used, but inconsistent

- v3, which was structured but impractical Neither felt like a real solution.

Taking a “fresh look”

Recognizing the gap between v2 and v3, HL7 launched the Fresh Look Initiative, an effort to rethink healthcare data standards from the ground up. The goal was to start clean, without being constrained by the limitations of earlier versions.

Two major approaches came out of this initiative:

1. CIMI – Clinical Information Modeling Initiative

Led by Stan Huff, CIMI aimed to create detailed and formal clinical models. It used traditional modeling methods to represent healthcare data precisely and in depth.

2. Resources for Health – Grahame Grieve’s Idea

Grahame Grieve looked outside of healthcare and saw how modern tech companies were building APIs, which were simple, RESTful, developer-friendly tools. He looked at products like Basecamp’s Highrise CRM and thought:

“Why can’t healthcare data work like this?”

Instead of creating massive models, his idea was to break healthcare data into simple, modular [resources]. These included things like Patient, Observation, and Medication. The goal was to allow systems to access and exchange them using lightweight APIs.

That idea became Resources for Health.

If you’re new to FHIR and want to build a solid foundation, check out our FREE FHIR Fundamentals course.

It’s a free, hands-on program designed to guide you through the basics with videos, articles, and exercises which is perfect for anyone starting their FHIR journey.

From idea to industry standard

Once the HL7 community supported Resources for Health and agreed to make it open source, momentum grew, and the project eventually became FHIR.

It quickly became clear that this approach simplified things for developers and vendors. It used common web technologies (REST, JSON, XML), was modular, and didn’t demand deep domain expertise just to get started.

Where FHIR stands today

FHIR is a popular healthcare interoperability standard today. To understand how it fits in, read our article on the 4 levels of healthcare interoperability. It’s even included in laws like the U.S. 21st Century Cures Act, which requires healthcare providers to offer API access to patient data and those APIs must use FHIR.

Healthcare organizations, EHR vendors, and governments are all using it or moving toward it.

For more insights into Grahame’s vision and the future of FHIR, watch The Future of FHIR with Grahame Grieve, an interview where he covers

- FHIR’s origins

- FHIR’s key milestones, and

- FHIR’s impact on healthcare interoperability Grahame Grieve also highlights how FHIR’s simplicity and adoption by US vendors and Apple helped drive its success.

Quick recap

FHIR wasn’t just another version of HL7 but a complete rethink. It took lessons from what failed, kept the parts that worked, and borrowed ideas from how modern software gets built today.