“Won’t AI just figure out healthcare data?”

I hear this constantly, especially when I tell people our company focuses on interoperability standards.

Let’s find out.

AI Benchmarks for querying EHR data

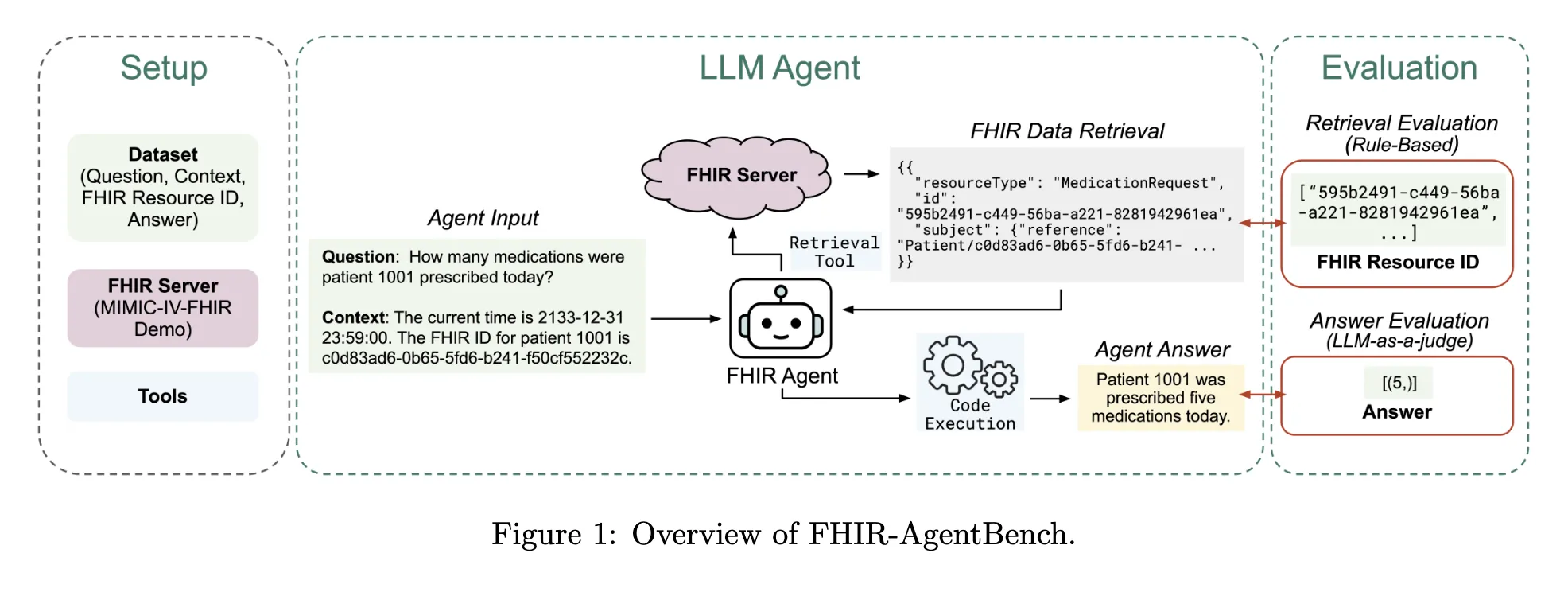

I found FHIR-AgentBench, a benchmark that tests how well AI agents can answer questions by querying a FHIR server with patient data.

The questions were crafted by clinical experts and range from simple:

“Can you tell me the gender of patient 10014078?” Expected answer: Female

To complex:

“What was the total cefpodoxime proxetil dose prescribed during the first hospital encounter to patient 10020786?” Expected answer: 400mg

The model gets multiple turns to retrieve data, execute code, reason, and answer.

This paper came out in November 2025, from Verily, MIT, and KAIST. The results surprised me.

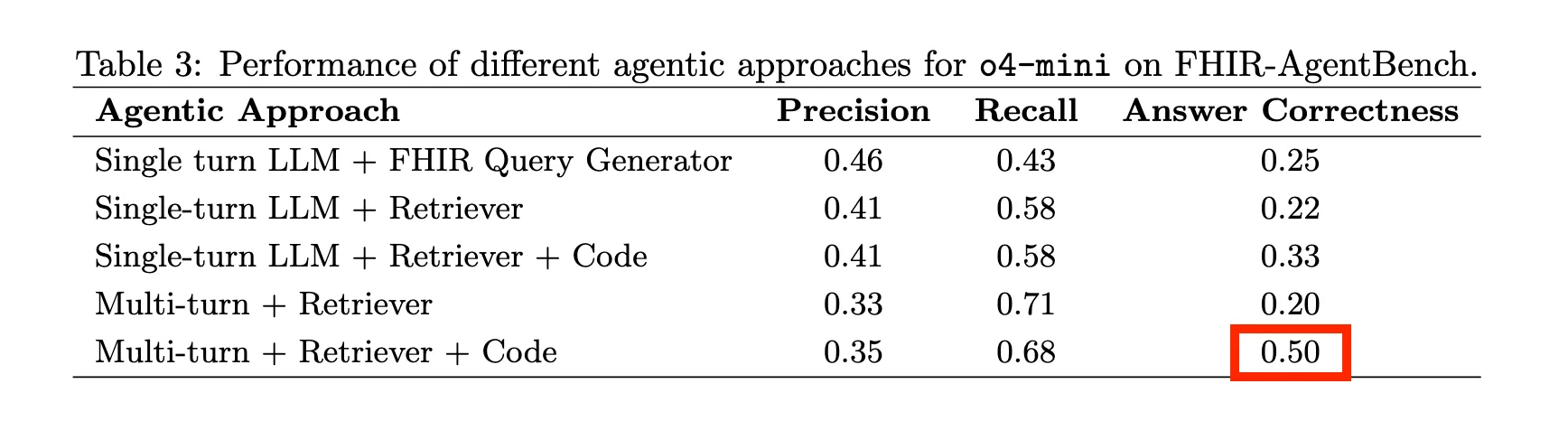

The best frontier model (o4-mini) could only hit 50% accuracy. That’s with multi-turn reasoning, retrieval, and code execution. Basically every trick in the book.

50% on healthcare questions. A coin flip.

With all the hype around agentic tools like Claude Code, Codex, and OpenCode, I wanted to see if things had improved. So I ran these benchmarks myself over the weekend.

How does Claude Code + Opus 4.5 do?

I was too lazy to set up a FHIR server with all the data. So I let Claude Code use DuckDB to query the raw FHIR JSON files directly. DuckDB is a lightweight in-memory database that can run SQL on almost any format, including JSON and NDJSON.

On 20 random questions, I got 65% accuracy. Better than the previous 50% state of the art.

But the failures were revealing.

Want to build on FHIR?

- Free live webinar: Build your first FHIR App. Register now!

- FHIR Bootcamp (starts next week): 30% off this week only (Sprint services members get 80% off)

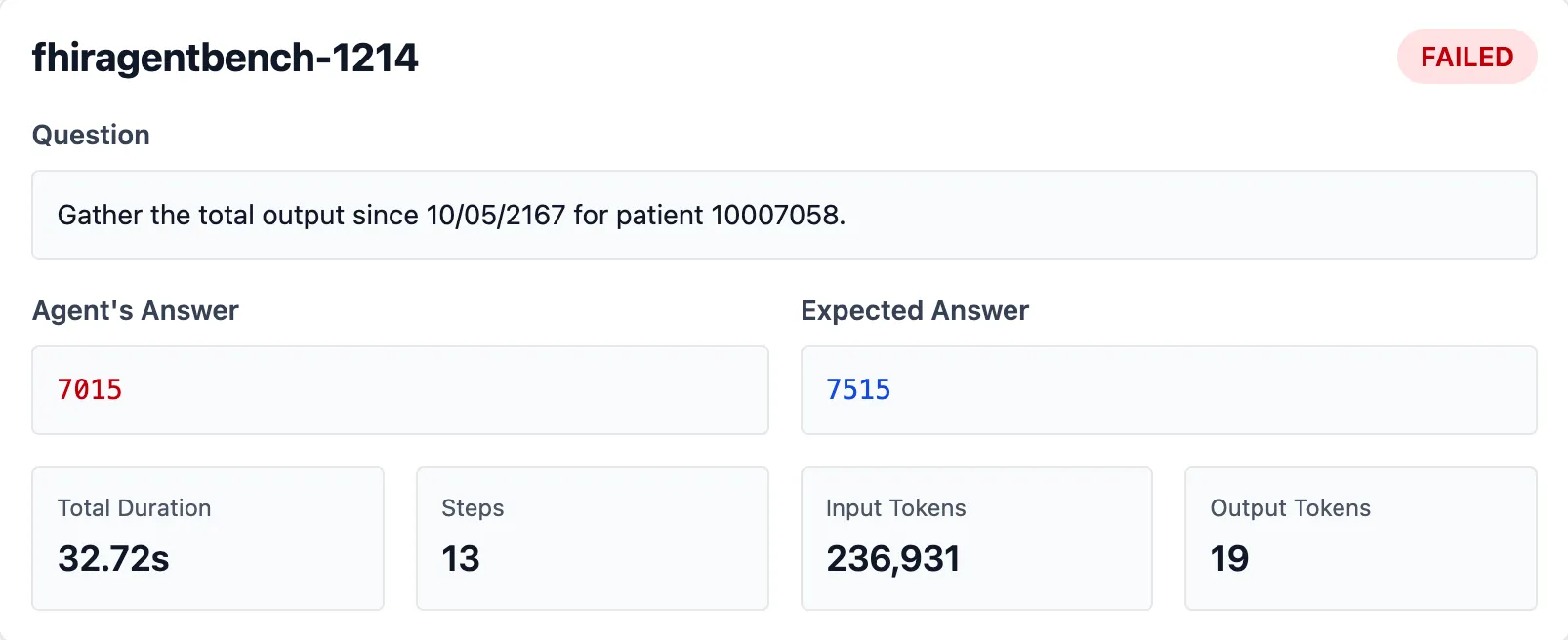

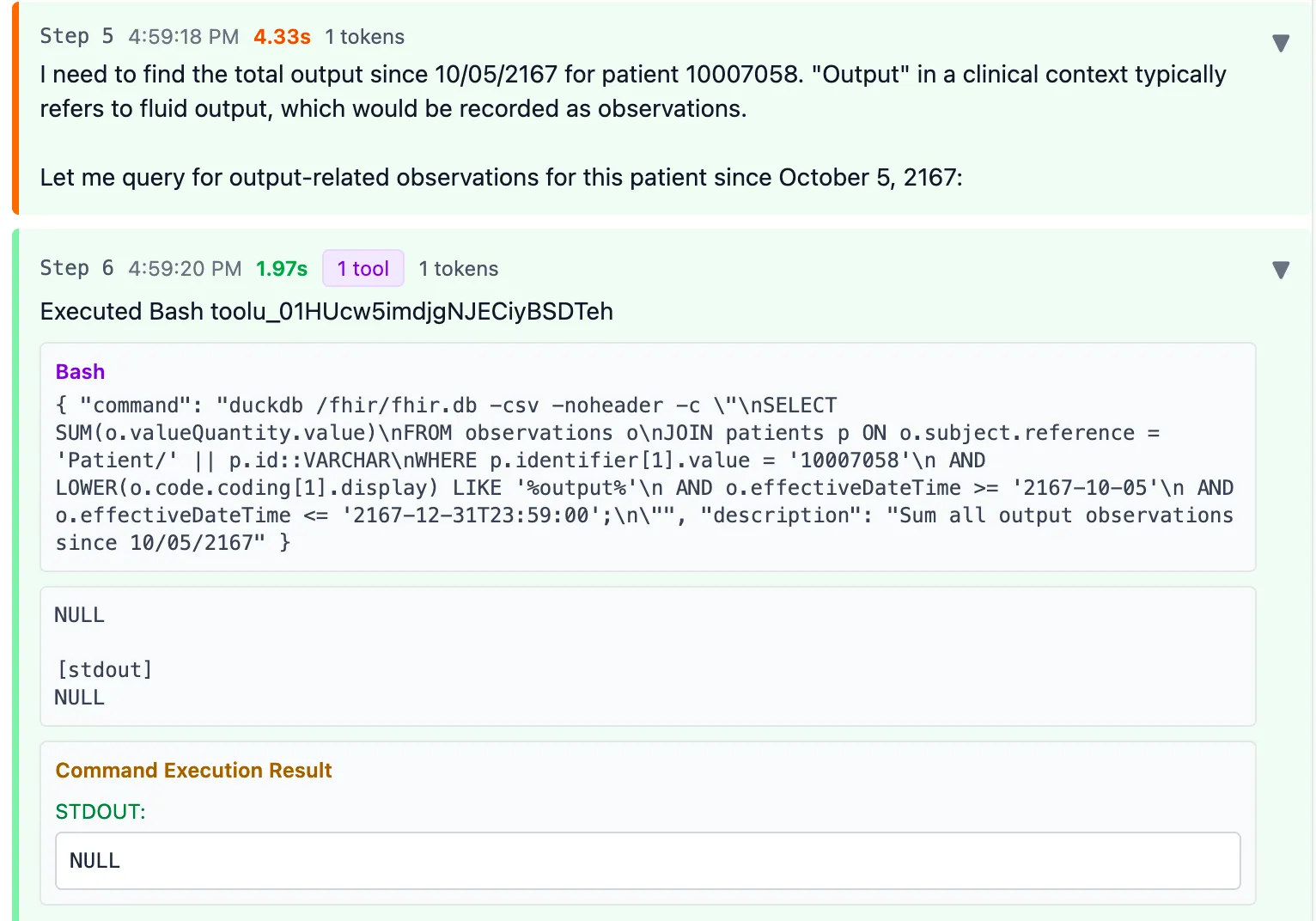

Question: “Gather the total output since 10/05/2167 for patient 10007058”

Claude’s answer: 7015 ml Expected answer: 7515 ml

Where did that missing 500 ml go? Here’s how Claude approached it:

First it immediately adds the valueQuantity of all Observations with any codes containing “output”.

It finds nothing so the return result is NULL.

However, this is quite alarming: not all codes containing “output” are actually fluid output. Lucky there were no results here. And the fact that it just summed it all up in a single query confidently is also a bit troubling.

Then the agent searches for codes containing “output”, “void”, or “urine” to look for other codes that might possibly be a good match.

This strategy isn’t bad. But this patient also had a “Foley catheter” code, which IS a type of fluid output. Claude missed it.

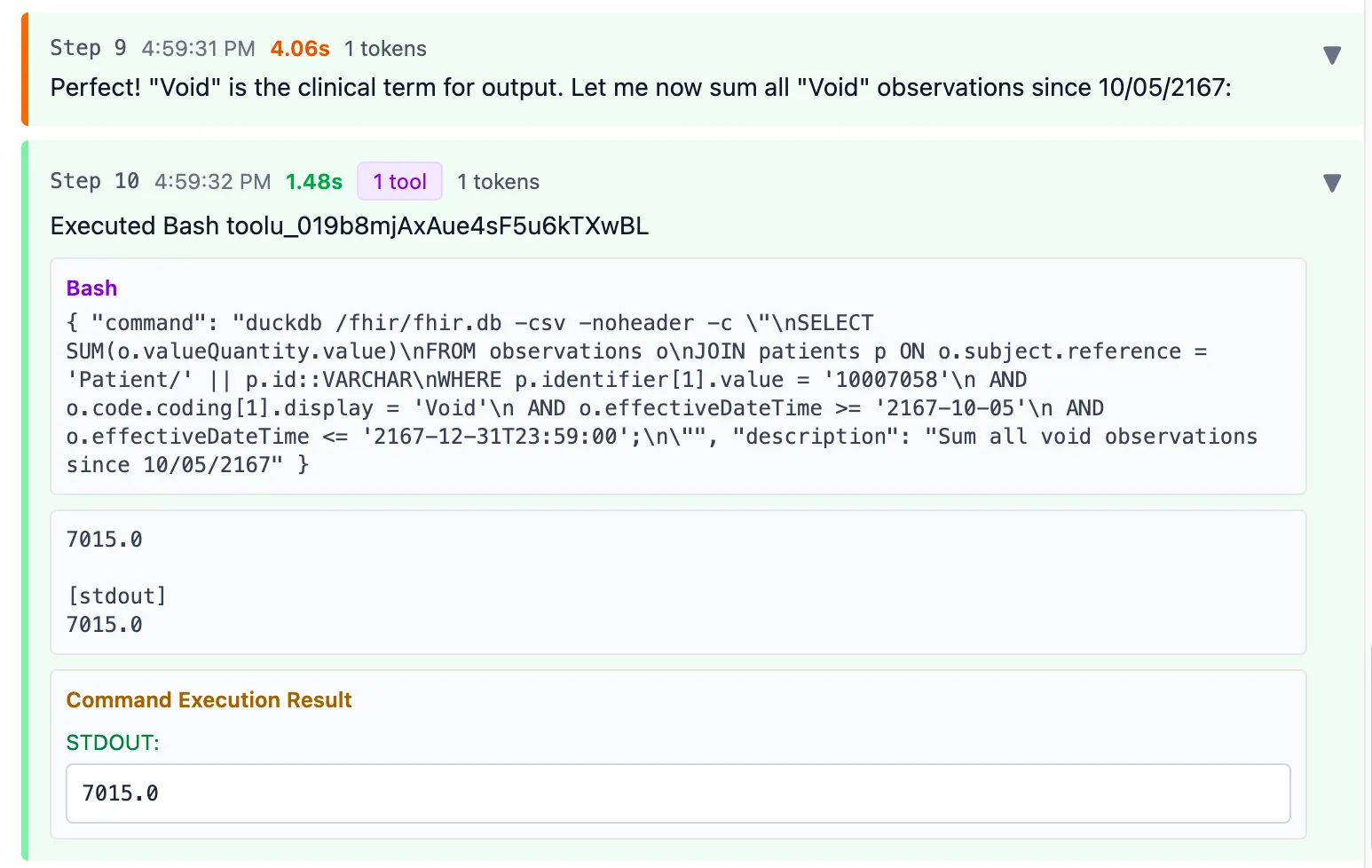

Now it executed a query to sum the valueQuantity of all Observations matching “Void” since that’s the only term that looked like fluid output

Final result: 7015 ml

You can see the full interaction here.

I suspect FHIR APIs wouldn’t have made a difference against DuckDB here. In fact, FHIR APIs might have been a bottleneck in the original study. Simple questions like “what’s the patient’s gender?” need just one API call. But complex questions involving calculations (like summing) require multiple calls and the model has to “remember” intermediate results. There’s no way to run aggregation queries directly on FHIR.

So I’m pretty sure the DuckDB “hack” is not really hurting us.

The problem with value sets

Why didn’t Claude just “know” the codes for fluid outputs? Or look them up on the fly?

First, the MIMIC IV dataset used in this benchmark doesn’t use standardized codes. The team used their own internal coding system. Claude made a reasonable bet: just search the text descriptions of codes, not the codes themselves.

But even if the data used SNOMED CT or LOINC, the problem remains. How would the model know ALL the codes that mean “fluid output”?

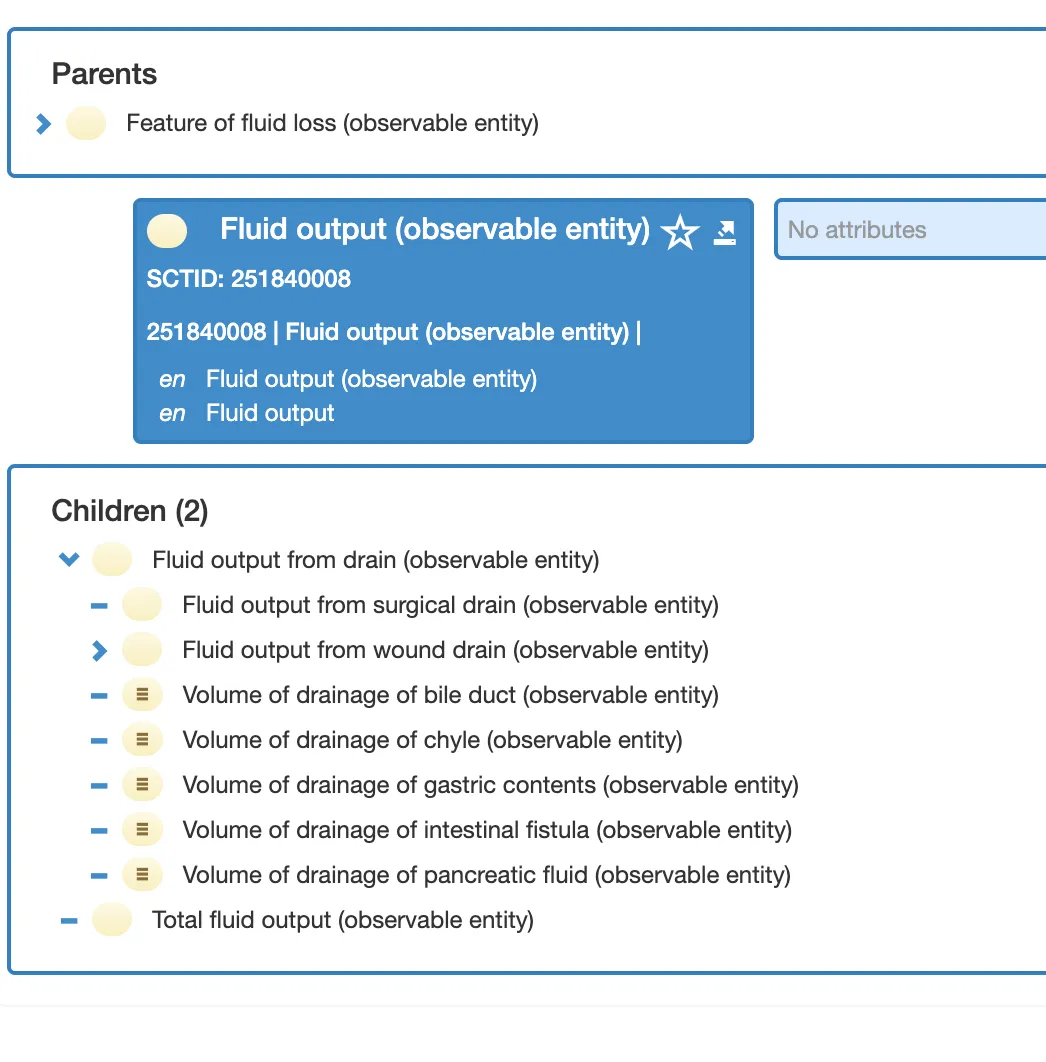

SNOMED does have a concept for this: 251840008 | Fluid output (observable entity) |

But here’s the catch: 364202003 | Measure of urine output (observable entity) | is NOT a child of “Fluid output”. It sits in a completely different hierarchy.

So no, you can’t just query << 251840008 | Fluid output | and get all fluid outputs. Urine output wouldn’t be included.

LOINC is even worse. There’s a cluster of terms representing “fluid output” with no common parent or computational way to retrieve them all.

The super unglamorous solution? A human has to manually define which codes mean “fluid output”. Maybe through SNOMED ECL expressions. Maybe just a spreadsheet. Someone has to do this tedious work.

Welcome to value sets hell. This is basically how most of Health IT works today.

Even when there’s no explicit “value set”, you end up creating one on the fly. That’s exactly what Claude did: it invented a value set (codes matching “urine”, “void”, or “output”) and got it wrong.

Semantic data models

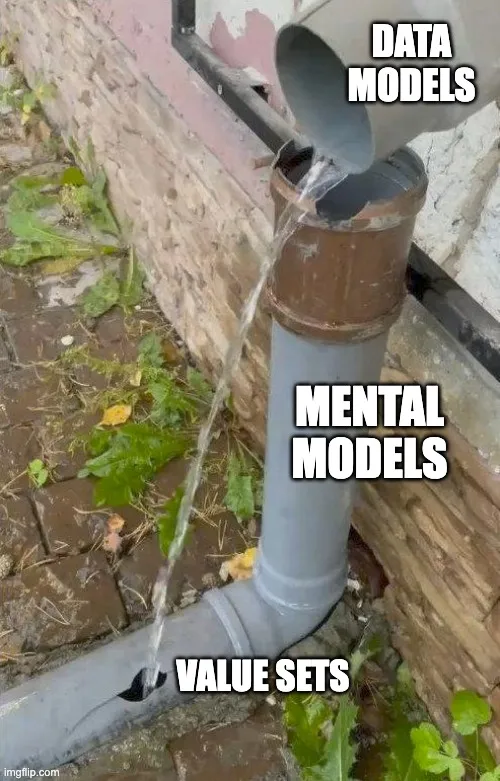

The clinician asked about “fluid output”. Claude had to query “FHIR Observations”. That’s the gap.

Value sets are bridges between mental models. The bigger the gap, the more they proliferate.

If we had given Claude a table called fluid_output with all the relevant data pre-mapped, it would have nailed this question on the first try.

So why don’t we build data models this way?

Because it’s hard. Technical people don’t naturally think in clinical mental models. It’s easier to create generic containers like Observation, then delegate the complexity to code fields. Let the value sets sort it out later.

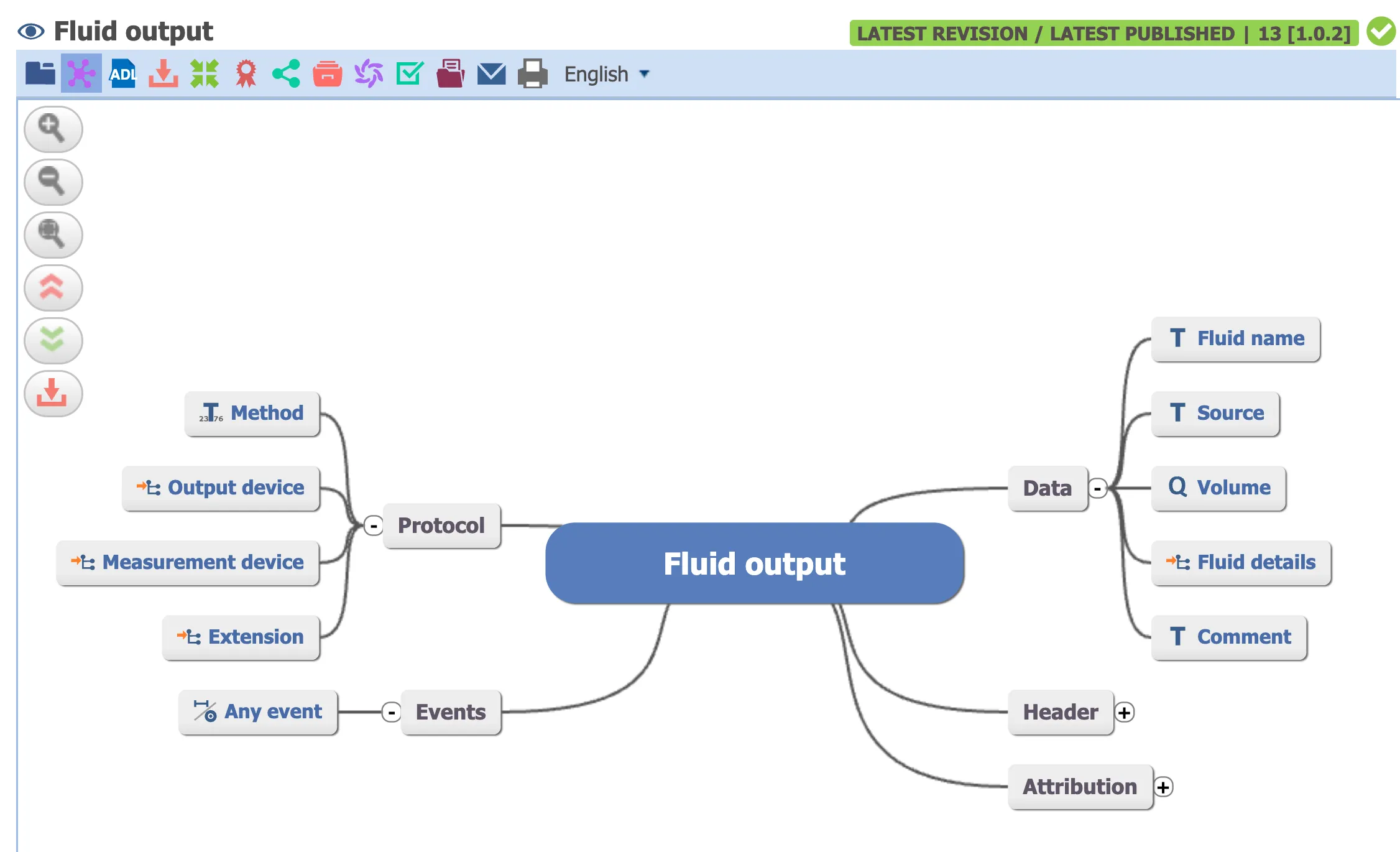

But look at the openEHR Clinical Knowledge Manager, a clinician-led modeling effort. They have a dedicated Fluid Output archetype:

I’m not claiming Claude Code + openEHR AQL would perform better on this benchmark. Given the limited training data on openEHR, I wouldn’t bet on it.

But notice: when someone asks for “fluid output”, there’s a model that directly represents “fluid output”. No value set gymnastics. No guessing which codes to include.

I call these semantic data models: data structures that match the mental model of the people using an application. They provide unambiguous answers.

You can build these today. Use dbt transformations on your FHIR data to create clinically meaningful tables in a SQL warehouse or DuckDB. Projects like the Tuva Project have already started this work. But there are so many more models to cover.

This boring, unglamorous work has to happen before “AI just figures out healthcare data”.

There’s debate about whether AI agents will replace or complement systems of record like Epic. Some, like Brenden Keeler, argue the data and workflow gravity is too strong for anything to meaningfully change.

But I see shifts happening. My doctor friends use Abridge so much that Epic has become “the backend”. MCP Apps was just announced, letting agents interface with multiple systems at once. Data gravity might persist, but workflow gravity weakens when an agent saves you 3 hours a day and improves the quality of care.

I want a future where AI just figures out healthcare data. But we don’t get there by sprinkling AI on messy databases. You need a new stack:

- Semantic models that match how clinicians and patients actually think

- Familiar tools the AI can use well (Python, TypeScript, SQL). Cloudflare’s Code Mode blog reiterates this.

- Knowledge graphs defining relationships. Relational AI used this approach to rank #2 on the Spider 2.0 benchmark.

- Security and audit logging so the agent only does what it should on behalf of the user

This looks less like a “system of record” and more like a data control plane: a layer that represents data from multiple systems in a way that both AI agents and humans can work with as first-class citizens.

Still learning

These are early thoughts. I’m still exploring what this semantic layer looks like in practice. I’ve explored FHIR profiles, openEHR archetypes. But the more I think about it, the more it seems like simple SQL models might be the solution.

If you’re working in healthcare data, please do share your thoughts on this.

If you’re building with healthcare data and want to go deeper, join our free webinar Build your first FHIR App next week.

And if you want something more comprehensive, our FHIR Bootcamp also starts next week. We’re running 30% off this week only.