Why openEHR? Explained

Before diving into the technical details of how to work with openEHR, it’s useful to understand why openEHR exists in the first place and the context in which it makes sense.

In the early days of computing, people who used computers often also wrote the software themselves. There were no mature operating systems or ready-made applications. Basic tasks like scheduling required custom programs.

When hospitals first started using computers, each hospital built its own software for scheduling, storing medical records, and managing medications. Large hospitals had dedicated teams who understood these systems and maintained them. Surprisingly, this worked quite well for a while. There are even early papers, like those describing “chartless medical records,” that show how advanced some of these custom systems were.

Over time, computers became cheaper and more widely available. Buying hardware was no longer the main challenge and maintaining software became the expensive and complex part. For most small and medium-sized hospitals, building custom software was no longer practical. Instead, they began buying off-the-shelf systems from vendors. This led to the rise of “best-of-breed” software.

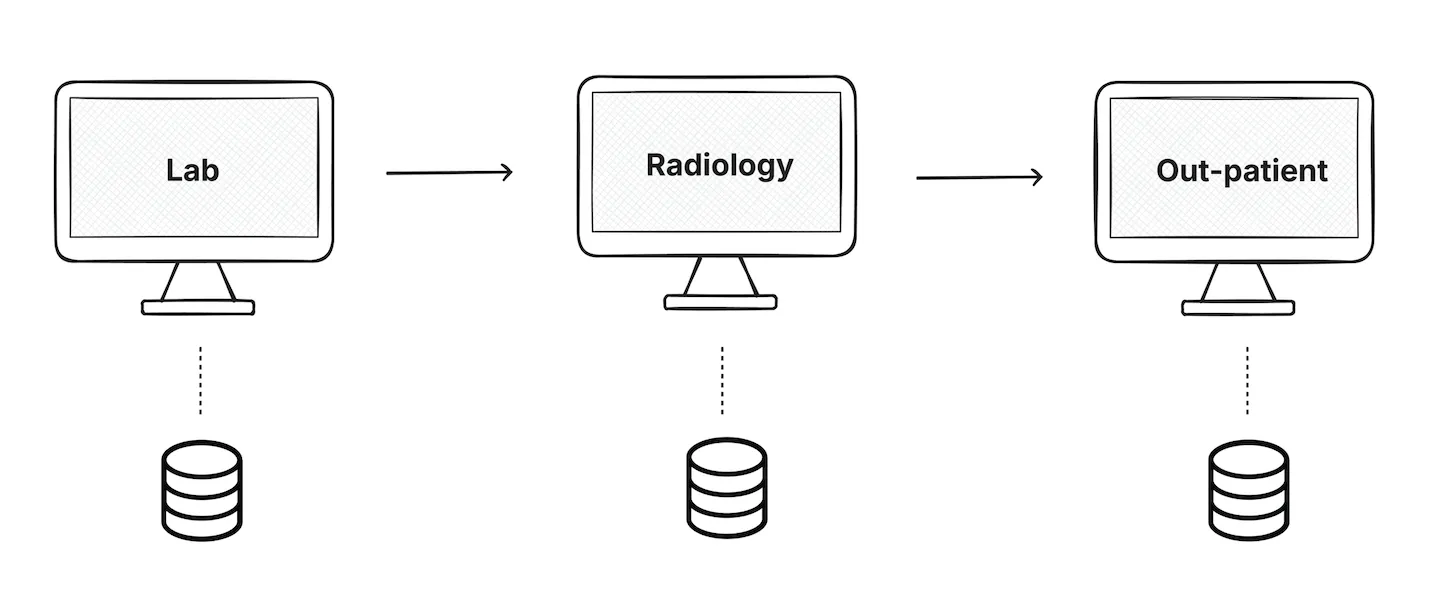

Hospitals started using a different system for labs, radiology etc. Each system did its own job well, but the data was in silos. These systems didn’t naturally work well together and as a result the same patient information was entered multiple times.

This problem still exists today in many hospitals.

This is where single vendor EHR systems enter the picture.

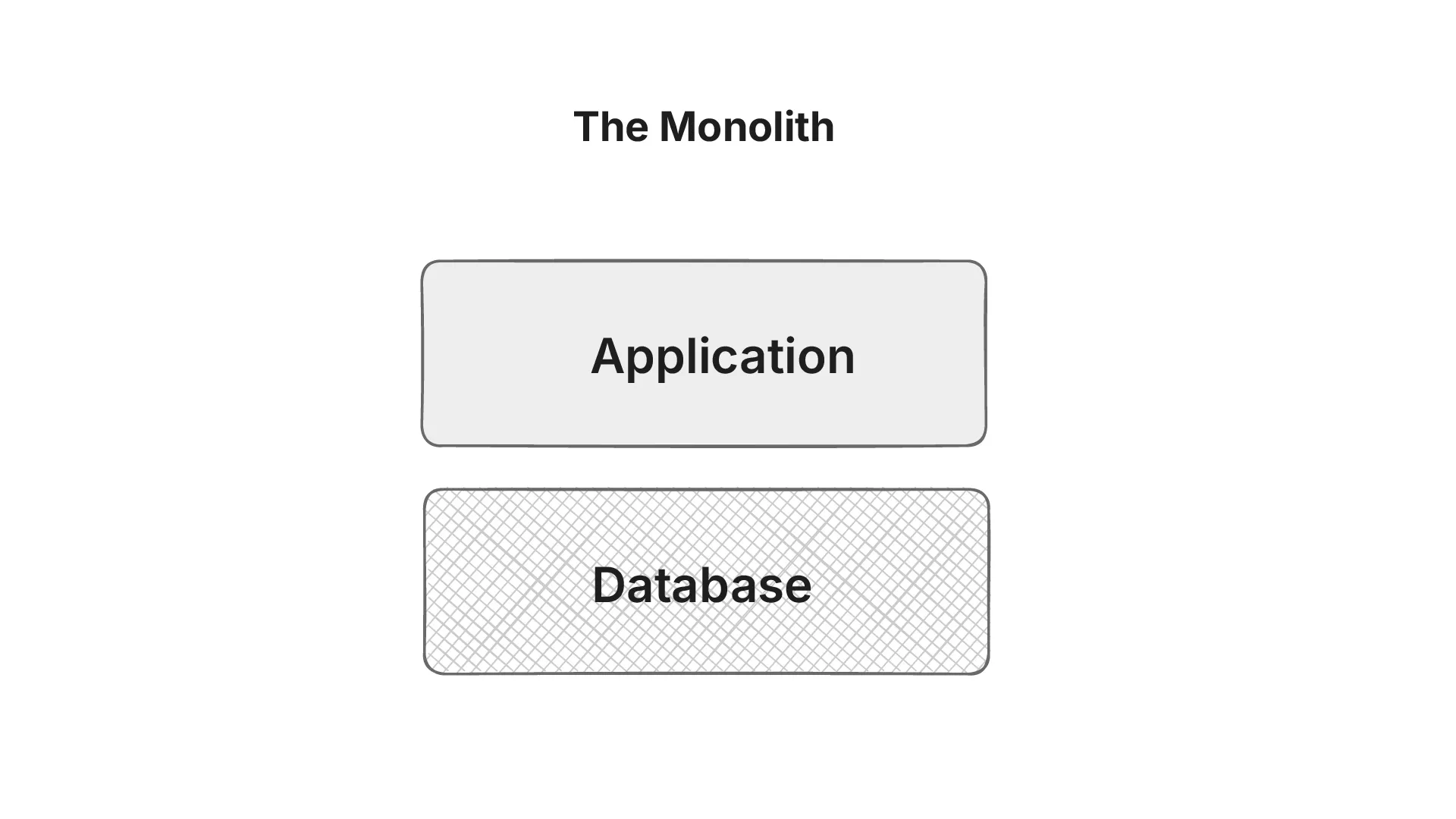

Monolithic Systems

At this point, hospitals were under real pressure to implement an EHR. In the US it wasn’t optional anymore. Policies like the HITECH Act even paid hospitals to adopt EHR systems. If you didn’t have one, you simply wouldn’t get reimbursed.

This is when large vendors, like Epic, stepped in and offered a very appealing promise: “We’ll handle everything for you.” They provided one system with multiple modules all designed to work smoothly together.

On the surface, this looked like the perfect solution. Today, many new hospitals still choose these all-in-one systems.

But over time, the downsides start to show.

Hospitals slowly realize that all their data and workflows are locked into a single system. Patient records, clinical work, doctor workflows, everything lives inside the vendor’s platform. When the hospital wants to do something new like run research, extract data, or change how part of the system behaves, they have very little control. They have to wait for the vendor to decide if and when those changes will happen.

In practice, this means the hospital doesn’t fully own or control its data. A huge amount of time and effort goes into maintaining a system of record that the organization itself cannot shape.

In the US, this problem became so serious that the government had to step in. Laws around information blocking were introduced to stop EHR vendors from restricting access to data. Patients now have a legal right to access their own health information, and EHR systems are required to allow that access.

This marked another shift in how healthcare organizations started thinking about data ownership and control.

Interoperability is another area where monolithic systems fall short. They were not designed for the API-driven world. Integrations that should be straightforward become expensive, custom-built projects requiring significant technical expertise. Moreover, because these systems were built around generic workflows, hospitals are forced to adapt their clinical processes to fit rigid software structures. Customization is rarely feasible, so clinicians end up working around the system rather than with it.

As healthcare evolves, monolithic systems are increasingly out of sync with the broader ecosystem. The industry is moving rapidly toward open, standards-based models such as FHIR, openEHR, OMOP, and national health information exchanges that enable data portability and long-term interoperability.

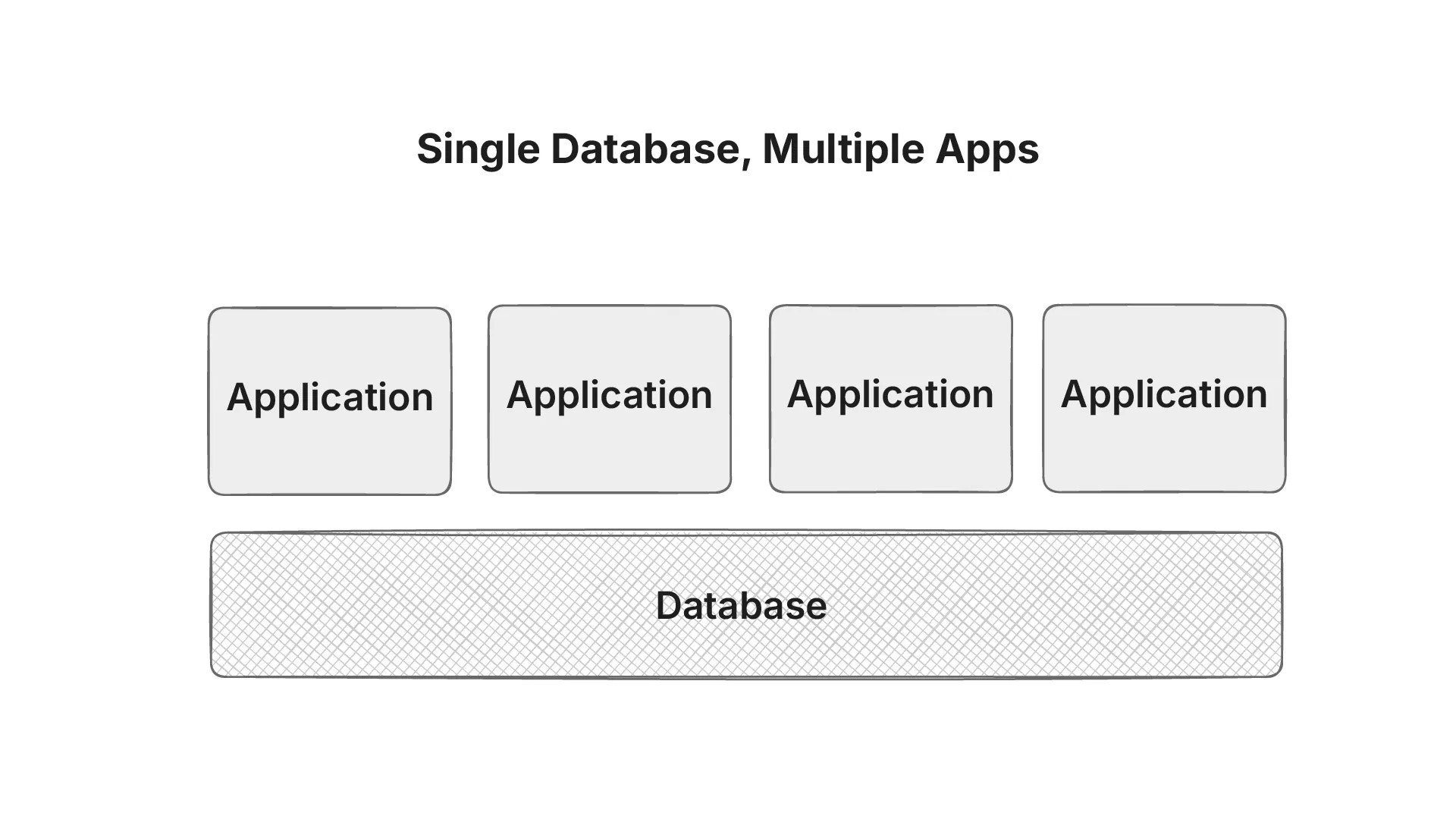

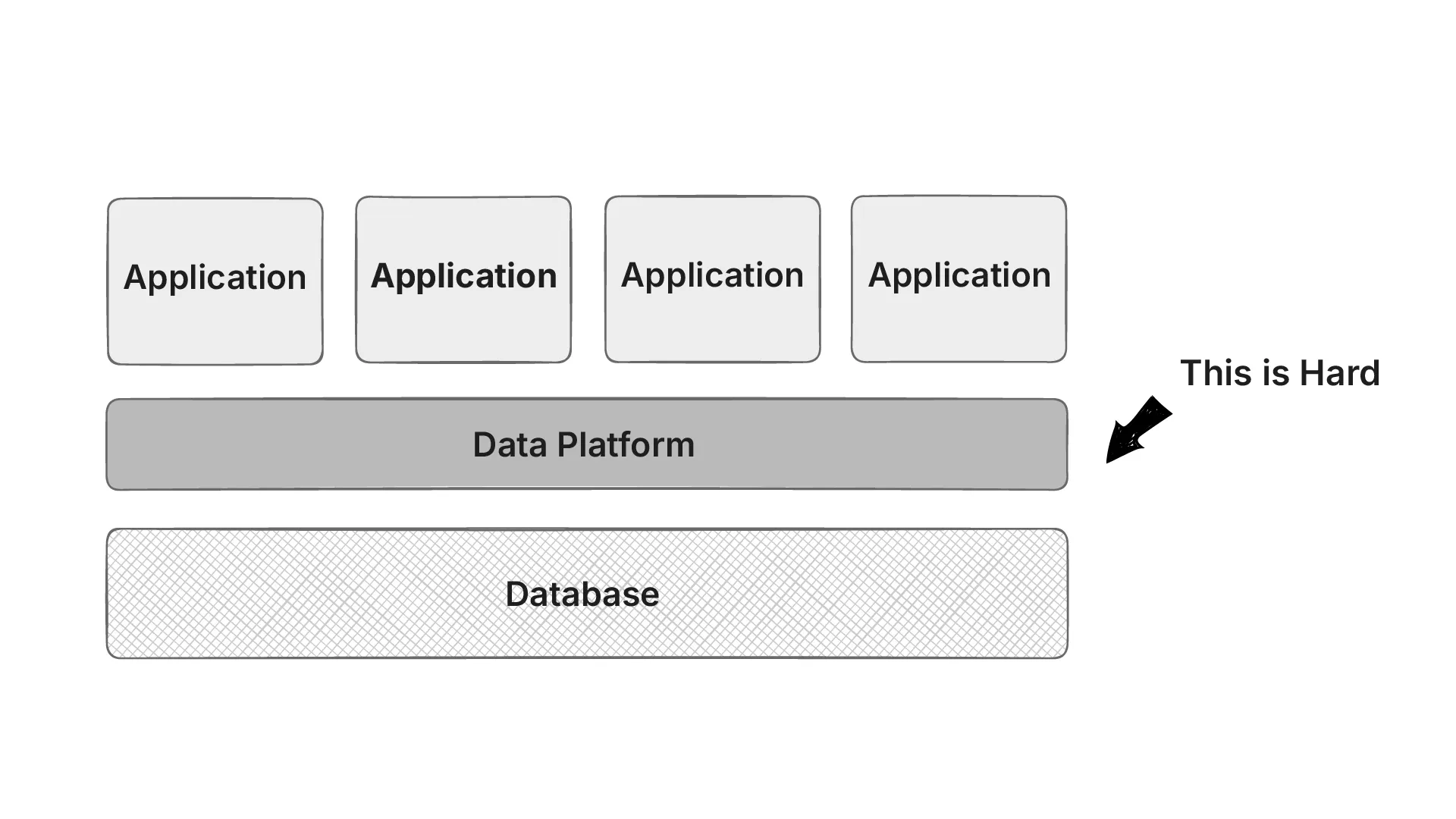

Multiple Applications Sharing a Database

In a shared database architecture all apps depend on the same schema. A simple change such as renaming a column or altering a table structure can break another app unexpectedly. This tight coupling between services creates fragility, making it difficult for teams to evolve their applications independently.

The database itself becomes a single point of contention. When multiple applications query the same database simultaneously, performance often degrades across the board. What starts as a shared resource for convenience quickly turns into a choke point.

This architecture also slows down innovation. If App A’s team wants to evolve faster, they’re limited by App B and C’s reliance on the same schema. Coordination overhead increases because every change “requires a meeting”.

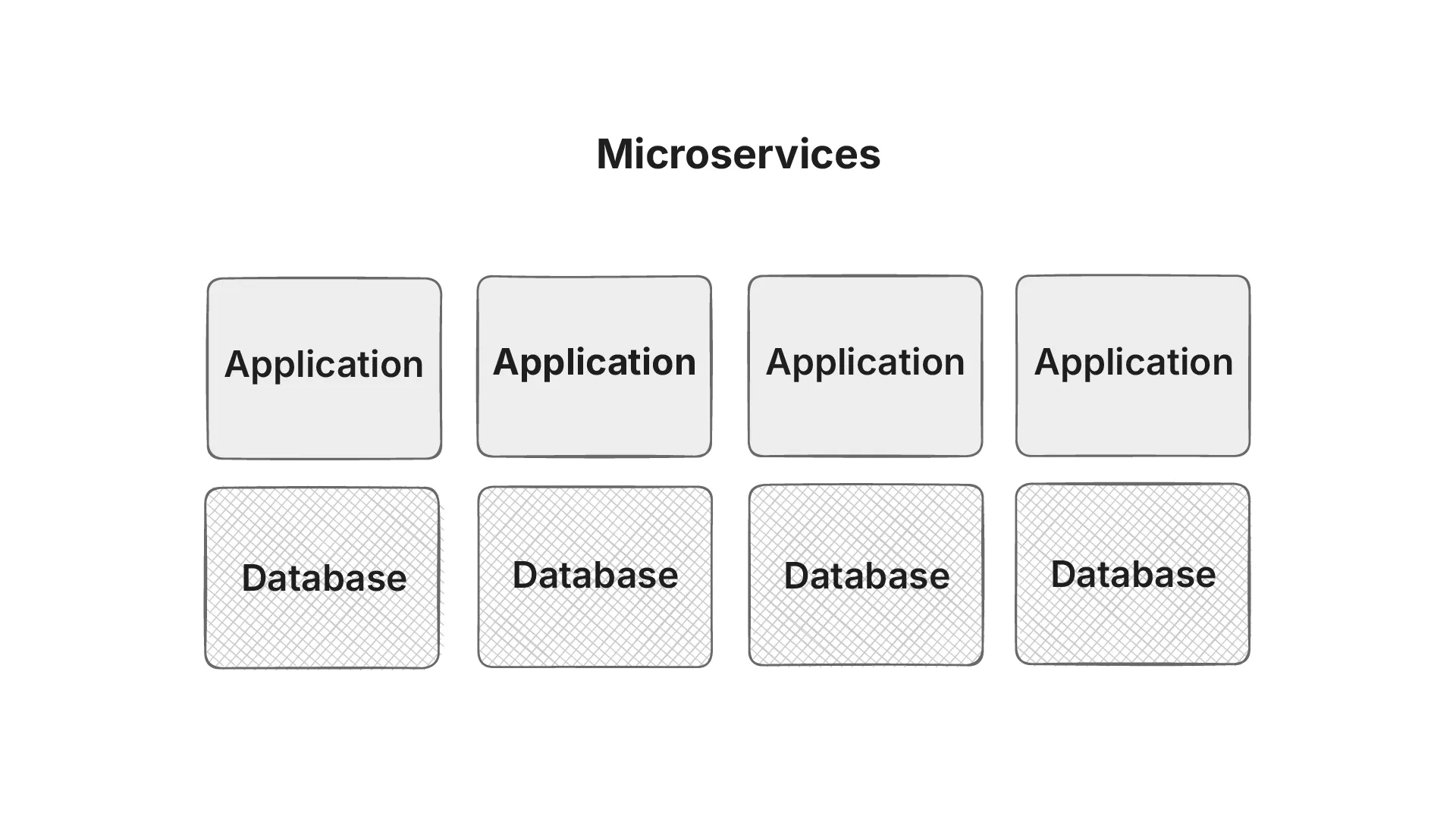

Microservices

Microservices in healthcare promise agility, modularity, and resilience, this works upto a point because the apps talk to each other through REST interface or their own bespoke API, but:

- Interaction via bespoke APIs: If you had n systems, you needed n × (n – 1) connections to make them all talk.

- They fragment patient data (longitudinal health record vs data silos).

- Lifespan of the application itself is much shorter (gets outdated every 10 years) than the lifespan of a patient. Which in turn increases operational and compliance costs.

Unified Data Platform

A unified data platform acts as a single source of truth in healthcare, bringing together information from EHRs, labs, imaging, pharmacy, and even wearables. Instead of clinicians jumping between systems, all data is consolidated into one longitudinal patient record.

Better clinical outcomes depend on complete and consistent data. Without unification, decision support tools or AI models risk missing context, like a critical allergy stored in another system. By harmonizing data, a unified platform ensures clinicians make evidence-based decisions with the full patient story in view.

We’re seeing the rise of FHIRnative databases or graph databases, but doing this is actually hard. We want the same information represented in the same way while allowing the applications to evolve and have their own set of requirements.

This is where openEHR shines.

openEHR as a Solution

As discussed previously, healthcare today suffers from fragmented, siloed systems that make it difficult to share and reuse clinical data. This has created a barrier for clinicians, patients, and innovators who need long-term access to data.

openEHR offers a solution by separating the clinical content from the technical implementation. It defines an open, vendor-neutral way of structuring health information using archetypes and templates. This ensures data remains consistent, reusable, and independent of any single application or vendor.

The strength of openEHR lies in its “semantic persistence” data stored once can be interpreted and reused decades later. Because the clinical models are built and governed by a global community, they evolve with medical knowledge while keeping past records valid. This makes openEHR ideal for long-term patient care.

In the next module we’ll take a look at how openEHR solves the “hard” problem of building a unified data platform.