[Extra] openEHR Conversations with David Ingram and Rachel Dunscombe

Before openEHR became the global standard we know today, it began as a simple idea.

Healthcare data should live longer than the software it sits in.

This principle has guided openEHR from its origins in research to its role today in national healthcare programs around the world.

In this lesson, we bring together insights from Prof. David Ingram, the creator of openEHR, and Rachel Dunscombe, CEO of openEHR International. Their stories show how an idea born in academia became a practical framework that shapes digital health systems.

The early vision for modelling healthcare

David Ingram began his career as a theoretical physicist. He went on to manage complex engineering projects and earned a PhD in biomedical engineering from the University College London. In 1976, he joined St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London as one of the UK’s first lecturers in Medical Informatics, attempting to combine the fields of medicine and computers.

At St. Bart’s, Ingram and his team explored how principles from physics and engineering could be applied to understanding human physiology. They attempted to model respiratory dynamics, fluid exchange, and pharmacokinetics, treating the human body like a complex system, similar to modeling the weather. But unlike weather systems, medicine is full of exceptions, context, and uncertainty. Paraphrasing Prof. Ingram, it wasn’t ‘feasible or tractable’ to model in the healthcare domain at the time.

He changed his focus to a new question.

How do we model the information behind healthcare?

How do we design systems that can represent the knowledge clinicians use, and make it computable and shareable? How can we make this data last?

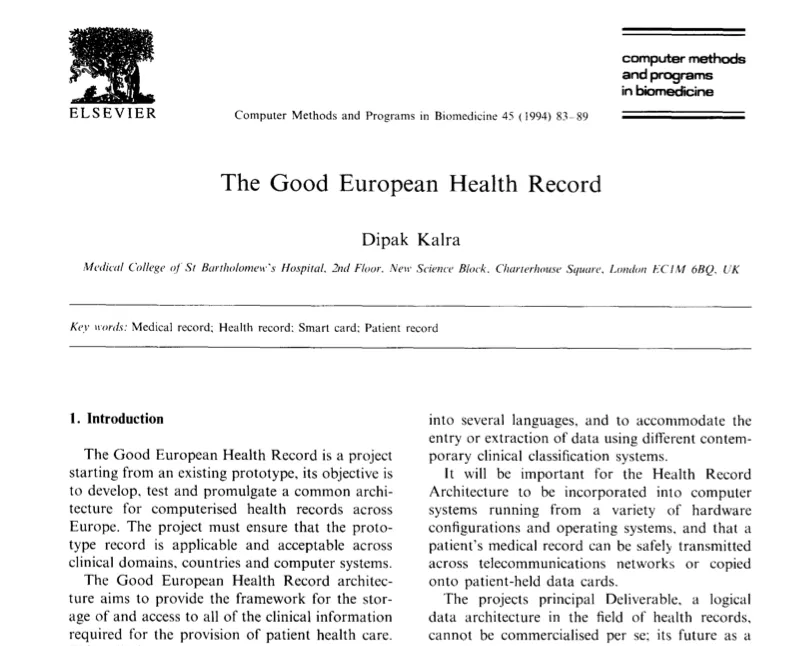

The Good European Health Record or GEHR

This question led to the Good European Health Record project or GEHR.

Launched in 1991 under the European Commission’s Advanced Informatics in Medicine programme, GEHR was one of the first international collaborations to design a common architecture for electronic health records. It brought together clinicians, engineers, and researchers from across Europe under Ingram’s leadership. Key figures, including Alain Maskens, Sam Heard, Tom Beale, and Dipak Kalra, were part of this.

Unlike many healthcare IT projects at the time, GEHR put clinical requirements first. The team recognized that healthcare data needed to be meaningful and carry context at every level. Ingram described this focus clearly:

A lot of the early work packages were about systematising requirements… from the very personal one-to-one to the more organisational and then population levels. The data needs to be credible, tractable, and relevant across different spaces.

From this work emerged the two-level modelling paradigm, one of openEHR’s defining concepts. It is a powerful idea to separate the fast-changing clinical knowledge from the technical software that stores it. That is, to define what the data means independently of how it is stored. This structure allows systems to evolve without losing meaning. While medical knowledge evolves and expands rapidly, the data model can adapt without the entire software stack needing a rewrite.

The ideas that emerged from GEHR would become the foundation of openEHR.

From GEHR to openEHR

By the mid-1990s, the ideas from GEHR had matured into a broader vision, and work began on a common healthcare information architecture. This led to the creation of the openEHR Foundation that formalised the two-level modelling approach into a set of open specifications.

Clinical knowledge was captured through archetypes, which were detailed, reusable models authored by clinicians. Technical developers implemented these archetypes in databases, applications, and services. This created a shared language between clinicians and engineers, where each group could work independently but remain connected through a common model of meaning.

Ingram often noted how much waste the old approach caused:

“It’s very easy to make the case that trillions of dollars have gone because data went into a black box. Systems failed, companies folded, and healthcare bore the brunt of it.”

Making openEHR real in modern health systems

The first time Rachel Dunscombe, CEO of openEHR International, encountered openEHR was when curating a TEDx conference in 2012. A clinician, Marcus Baw, wanted to talk about open standards in healthcare. It got Rachel very interested.

Some years later, she was the CIO of a large UK organization working on integrated care systems. It connected hospitals, community services, and social care and pushed models of care such as patient-led pathways, wearables, and self-reported outcomes. Traditional EMRs couldn’t store this type of information.

“When you’re trying to do integrated care, you suddenly realize the EMR is not fit for purpose, because it constrains what you can do. And it constrains your data model as well.”

To address this, she added openEHR to the EMR as an extension layer. It allowed them to have the full data model required for the models of care for the future. This marks her shift from managing applications to engineering data itself, a difference that would shape her thinking later on.

Thinking of data as infrastructure

Working with openEHR changed how Rachel thought about health IT altogether. It was important to build data systems that last. She now views data as part of the healthcare infrastructure.

“My analogy is we design hospitals now so that they are fit for purpose. They are a single big building with everything integrated: theatres near recovery, near everything else you need. We design it so it functions as a whole. Data is part of the infrastructure of the future. It’s like the elastic walls of a hospital or healthcare system. And we need to design it so it’s fit for purpose.”

This means thinking beyond technology cycles and engineering data for longevity. She argues for building data that will last decades or millennia. “At the moment,” she says, “we buy the cheapest thing and the data is an afterthought.”

Designing for safe interoperable systems

Rachel’s work with integrated care also made her acutely aware of the risks of poor interoperability. As health systems digitize, they also become fragmented. Integrations are often fragile, one-of,f and distort the meaning of data. This brings in safety concerns. The more data is transformed, translated, and re-interpreted between systems, the greater the chance of clinical risk.

That’s why, as CEO of openEHR International, Rachel began working to bring the wider standards community closer together.

“The JIC is really a group of standards bodies that work in healthcare. You’ve got the likes of HL7, SNOMED, LOINC, ISO… and we’re working closely with some of those bodies as well.”

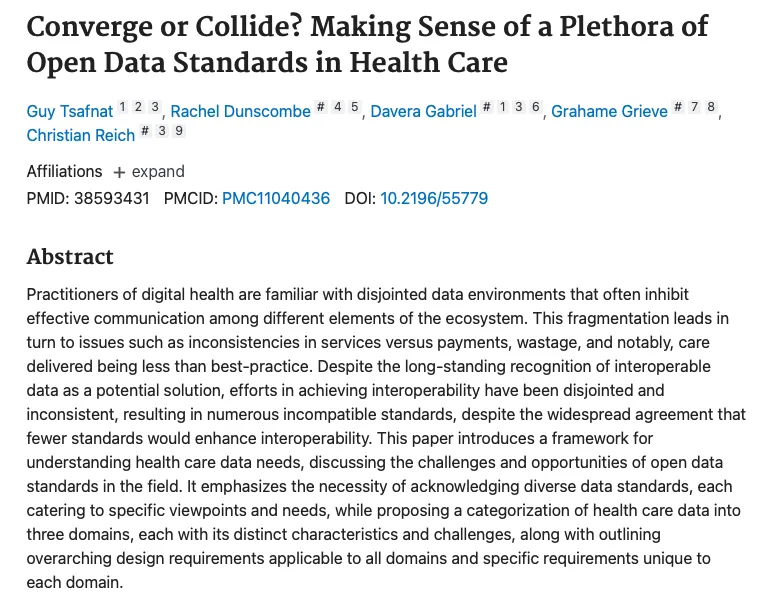

A joint paper published in early 2024 by the leaders of openEHR, OMOP and FHIR is testament to this committment to work together.

Her experience as a practitioner gave her a grounded perspective and helps her put into context why and how different standards bodies need to work together. Each standard has a different role to play in the larger interoperability space, whether it is data storage, exchange, or modeling.

“We’re really not competing, we’re complementary.”

And this defines the legacy she wants to contribute to, “to leave behind a set of blueprints or architectures that people can use to create really useful info-structures to save lives and improve lives”.

Data as the foundation of sustainable care

Every disconnected dataset has an impact on safety, health outcomes, and the economic stability of health systems. According to Rachel, data sustainability is healthcare sustainability. Well-structured, shareable, and long-lived data reduces waste, supports innovation, and extends the lifespan of every technology investment.

The health economics aspect of data is very interesting to her, and she has worked with the London School of Economics to build the economic case. This goes into her work at openEHR International, where she creates a community of people who believe in long-term, value-driven data stewardship. It is the shared values and open collaboration that achieve data sustainability. openEHR’s success lies in the growing network of clinicians, developers, and policymakers working towards this common goal.

In summary

In the 1970s, David Ingram began exploring how computers could represent the complexity of human health. His early work highlighted the difference between modeling medicine and physics, and the need for context in medical data. That insight became the foundation for the GEHR project. The two-level modeling approach used in openEHR was also developed at this time, to separate clinical knowledge from the technology that stores it.

Decades later, Rachel Dunscombe, working as a CIO in the UK’s early integrated care systems, encountered the same challenges in practice. Data was often trapped in rigid and proprietary EMRs and was unable to support new models of care. By adding openEHR along with the EMR, her team could represent richer and more flexible health data.

Both journeys converge on the same principle: that healthcare data should live longer than the software it sits in. openEHR is built on that idea and, beyond its spec, is a living, breathing community working towards the goal of sustainable and safe open healthcare data.